My eulogy for Twitter.

Twitter is dead, and letting go of the 14 years of my online life that I spent there is, at this point, the beginning of a healing process.

This article started out as a straightforward “Twitter is dead” post, but upon reflection I figured the world didn’t need any more of those—at least none whose main point is merely to autopsy its rotting cadaver. Watching Elon Musk run one of the world’s most important social media networks utterly into the ground in less than the time it takes me to go through a bowl of sugar has been an eerily fascinating form of rubbernecking, but the basics of that story are now well known. Musk has no idea what he’s doing; he’s a fascist enabler who wants to give free reign to the Nazis, TERFs, Trumpnuts and cryptoscammers with whom he shares his twisted world view; the $44 billion he’s thrown exuberantly to the winds in his purchase of this ultimately worthless asset will someday be cited as one of the most damning examples of self-ownage the world has ever seen. We know all that. Fortunately I’m not a journalist so the implosion of Twitter will likely have no measurable impact on my professional life, which means I don’t have to write a hand-wringing “Lordy, what will we do now!” type of post. (By the way, the answer is, go to Mastodon. It’s far superior). So this will turn out to be more of a personal piece than it started out to be.

I joined Twitter in its early days, not right at the beginning, but not far into its life. Back in the summer of 2008, when I made my first account there, Twitter was still known as the “microblogging” site, and it was hard to explain to anyone who wasn’t on it what you actually did there. I remember a mocking Facebook post from a friend of mine who didn’t get it. “Why do people need to document stuff so trivial?” he said. “‘Oh, I’m out of milk this morning! Twitter twitter twitter! My dog ate the TV remote! Twitter twitter twitter! I have to take a shit before work! Twitter twitter twitter!” It was fine. It did seem pretty silly, in retrospect. But it was fun. One of the coolest features was that you could update your status via text message. In 2008 I was incorrigibly addicted to text messages. Twitter seemed like a natural extension. I migrated to a new account in 2009, which eventually became my main home on social media.

Then, slowly, there came to be a community. I still remember the very first person I followed on Twitter. It was not a celebrity. I was curious to connect with fellow heavy metal fans, and when I searched for metal-related tweets, this guy was the first one who came up. I once met him in person. We had lunch together at a sushi joint. He’s a cool guy. That was how Twitter worked in the old days.

Twitter was awesome back then. It was decidedly low-tech by today’s standards. In order to retweet someone, you had to highlight their tweet, copy it and paste it into a new tweet of your own, and manually type “RT” and the person’s handle. Retweeting, in fact, was invented by the users of Twitter, not by the site itself. There were jokes about “Manuel Retweté.” Poor Manuel got killed off by the addition of a button, which admittedly made things easier, but I think there was value in the old system. You did a lot fewer retweets back then because they were much more laborious.

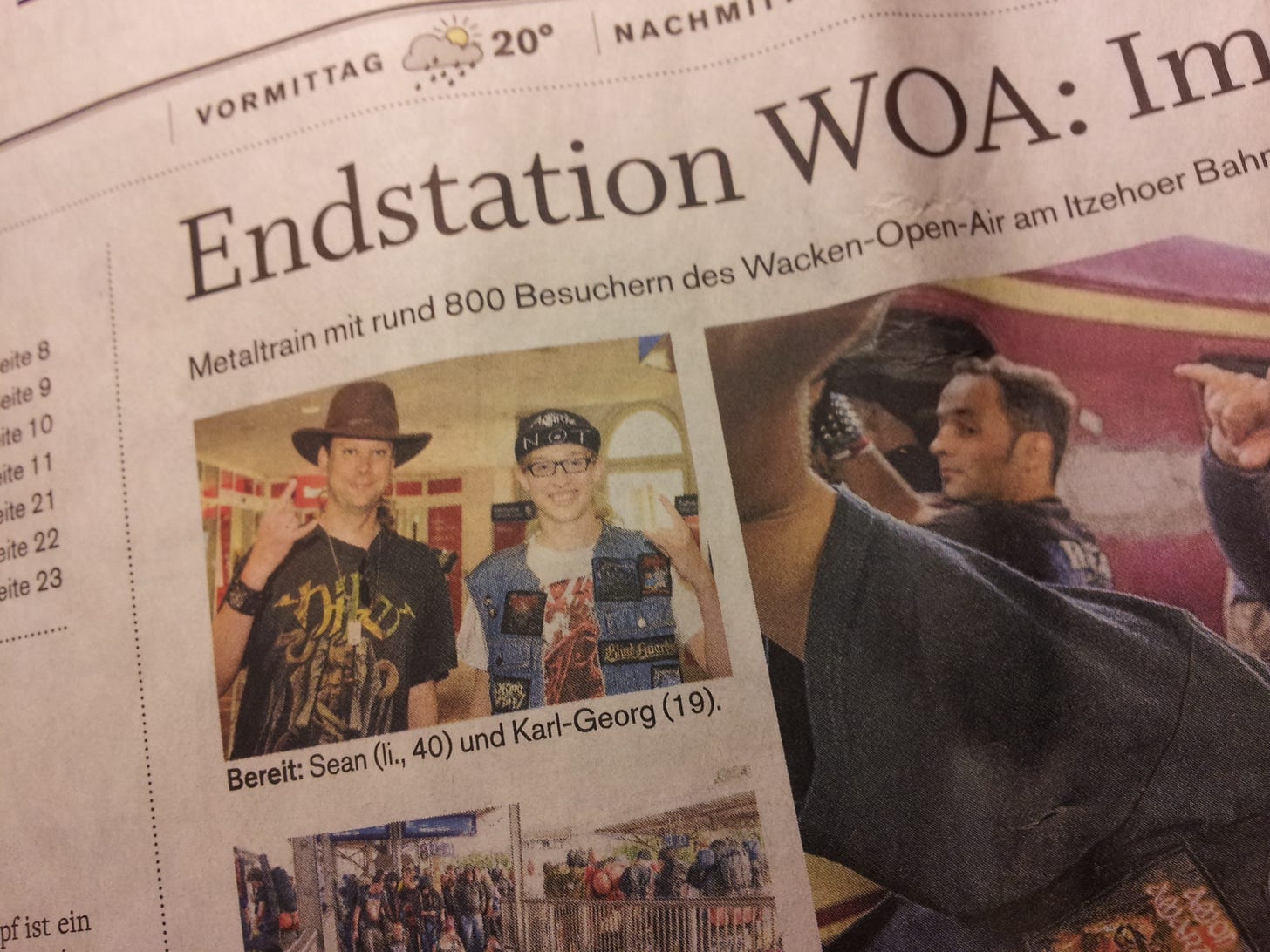

I met some great people on Twitter. One of them was a metalhead from Germany, Karl, who was 21 years younger than me. I met him in person too. We became acquainted on Twitter in 2013, and when we both went to the Wacken Open Air heavy metal festival in northern Germany, we met up and spent the festival together. In fact a reporter for a German newspaper, who was covering the festival, happened to be at the train station in Itzehoe when I first met up with Karl, and he was so intrigued by the story of how we became friends that he took a photo of us—which ended up in the newspaper. I still talk to Karl today. I count him as one of the great friends I’ve known in my life.

Twitter was not exactly democratizing—especially after the insipid blue check thing came in—but the brushes with celebrity were kind of fun. Over the years I interacted with George Takei, got a recipe tweeted at me by (pre-#MeToo) celebrity chef Mario Batalli, was bade a “Happy Sunday, Sean!” by Terry O’Quinn who played John Locke on Lost, briefly my favorite show; I was even blocked by celebrity Scientologist Kirstie Alley when I tweeted the word “XENU” (which Scientologists are forbidden to acknowledge). For a while in 2016 I suffered from a swelled head when I was quoted in the New York Times—a snippet from a historical article I wrote about the Presidential election of 1904—and sought to get a blue check myself, only to be told, “Yours is not the kind of account we typically verify.”

There was abuse too, even in the fairly early days. One incident stands out in my mind. In the summer of 2011 I posted a single tweet making fun of Libertarian politician Ron Paul, who was then running for President (or at least pretended like he was running for President). A Ron Paul supporter found the tweet and RT’d it. The firestorm of ferocious abuse directed my way from Ron Paul’s legion of rabid fans was still going on 26 hours later. This was a result of one tweet. It was nothing like the abuse that became commonplace later, especially for women and people of color, but I got a taste of it then. I thought it was an aberration, and I put it behind me quickly enough.

Then came GamerGate. I didn’t even know what GamerGate was at first, and had to have my husband explain it to me. GamerGate—a campaign of targeted misogynistic harassment against women and feminists in the video game industry—was, I think, the true inflection point of when Twitter began to become the net negative for the world that it unquestionably became. It tainted my memories of the way the platform used to be. One of my first follows in 2008 was a metalhead whose opinion on bands and albums I really liked. In 2010 he dropped out of sight, his account fallow, for 4 years. (I later learned he was in prison during these years). When he resurfaced, suddenly he joined the GamerGate bandwagon. Every tweet was a howl of rage against Zoe Quinn and Anita Sarkeesian intermixed with MRA propaganda. He never tweeted about metal anymore, and was toxic and unpleasant. He later deleted his account. In more recent years it has become clear that GamerGate was a primer for the rise of fascism. Had there been no GamerGate in 2014, I’m convinced Donald Trump would not have been elected in 2016.

The election, and Trump, seemed to bring out the worst in Twitter. In the late summer of 2016, during the Democratic National Convention when Trump attacked (on Twitter) the Khans, the Muslim family of an American soldier killed in Iraq, I expressed outrage about it. I got an @ reply from a guy I’d followed since 2009, and who I used to converse with a lot. I hadn’t heard from him in a while, but he had now, in the age of Trump, become a diehard MAGA groupie and a vitriolic hater of Muslims. I won’t repeat his racist tirade against the Khans, but it was pretty shocking. Just before I blocked him I wrote, “I’m disgusted that I ever followed you.” Indeed, I felt shamed, dirty, guilty for thinking, 7 years previously, that this kid on Twitter was funny and cool. There was no indication of racism then, but Trump—or the GamerGate grifters, or somebody—had poisoned him. I felt so awful, for him, for the sad and hateful mess he’d become, that I dreaded clicking that little blue bird on my phone. During this same time I was getting harassed. Anonymous accounts with Pepe the Frog avatars were @ ‘ing me crudely photoshopped pictures of my profile pic being shoved into a Holocaust crematorium, sometimes by a Pepe the Frog dressed in an SS uniform. This is what happened when you were Jewish on Twitter in 2016.

The Trump years were hell on the site. I blocked the bastard early on but it didn’t stop me from seeing the stinking sludge that he spewed across the site on a daily basis. One day in 2018 did an informal tally of how often a Trump tweet was quoted or referred to in the news sources I viewed on a daily basis. More than half the news stories that came across my news feed had something to do with Trump’s activity on Twitter. More than half! And half of those consisted of stories where a Trump tweet or series of tweets was the sole subject of the article. It was a reality distortion field, a black hole whose gravity was so strong that no one, even someone who didn’t want anything to do with Trump, could escape. I decided to quit Twitter. That was in October 2018. Rather than delete my account, which would have enabled my username (which was my name, with an underscore) to be picked up by someone else, I deleted all my tweets, unfollowed everyone except that very first metalhead I followed back in 2008, and turned my profile pic blank. It was hard letting go of the community and the friends, most of whom didn’t understand why I did it even though the evidence was right in front of them. It was the right move, but I missed Twitter.

On January 9, 2021, the day after Trump was banned—together with tens of thousands of Nazi, QAnon and other noxious accounts—I felt safe enough to return. It was something of a triumph: I was allowed to use Twitter, and Donald Trump and his sick friends weren’t. By 2021 I had learned to mass block bad actors using chain lists, and the site had introduced features to screen out at least some of the harassing tweets from sockpuppet accounts that had made the previous years so awful. But the essential features of Twitter that made it such a negative thing remained: the algorithm that was designed to serve up outrage, the quote-tweet dunkings of “bad takes” that became performative theater, the endless doomscrolling behavior. I willingly participated in these negative rituals. I didn’t even realize the extent to which they had taken over my psyche and come to dominate my online experience.

Then came Musk, the capricious man-boy, the destroyer of companies and a walking advertisement for the moral bankruptcy of capitalism. The rumors that he was coming started in the spring, and honestly even in late October 2022 I was paying little attention to the asteroid that was hurtling toward the herd of dinosaurs it was destined to destroy. The reality that Musk was going to bring back everything I most hated about the site—up to and including, especially, Trump and the Pepe brigade—was hard to swallow. But ultimately it wasn’t hard to decide to leave. The days of meeting cool people from Twitter at sushi restaurants and metal festivals were long in the past. GamerGate, the Khan-bashing MAGA kid, the 26-hour rants by enraged Libertarians and Pepe the Frog in an SS uniform were not aberrations. These things were and are the basic substance of what Twitter is, and I guess always have been. What I gained from once having been a part of it was far outweighed by the awfulness of what it truly was.

Now looking back on it, it’s clear to me that Twitter is, in a word, an abomination. It is a hate amplifier. It’s a ravenous roaring Moloch that feeds on human souls, sucking in goodness and community and shitting out hate, rage, resentment and negativity as its foul product. It doesn’t bring people together—it tears them apart and seeks to profit from their animosity. Elon Musk won’t make a dime on Twitter, fortunately, but if he somehow managed to, every dollar he could wring out of it would be soaked in the blood, tears and anguish of the people who, like me, were deluded for so many years into thinking we loved it and needed it. We can’t heal the incalculable damage that Twitter has done to the world. But maybe, by recognizing our own complicity in helping to cause that damage, we can heal ourselves, if only a little bit.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my book, which I wrote in part to take my mind off climate anxiety.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

💌 Feedback to share or want to say hello? Hit reply on this email or leave me a comment on Substack.