Scandals, burnt letters and bad crab meat: the death of President Harding.

What killed old Warren G.: a bum ticker, bad crab meat, or something else? We'll never know for sure, but he left a big mess behind.

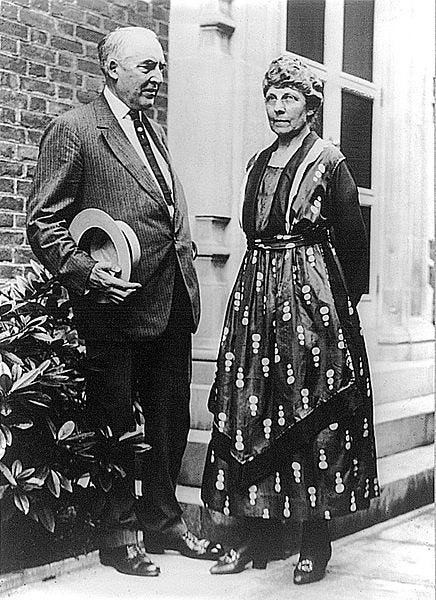

On the evening of Thursday, August 2, 1923, Warren G. Harding, 29th President of the United States, died suddenly in room 8064 in the Palace Hotel in San Francisco. He was the second President to die in office in the 20th century, the first to die west of the Mississippi and the only one to die in a hotel. The cause of his death has been disputed. Some medical experts believe it was a sudden heart attack. Others claimed it was a stroke. Harding's own doctor, who was more of a practitioner of homeopathy than a real doctor, said it was food poisoning caused by bad crab meat. All anyone could really agree on was the obvious fact that Harding was dead.

Personally and medically, Harding had been on a decline since the previous autumn. He seemed to get awfully tired, had difficulty sleeping and sometimes had chest pains. He was in San Francisco on an extended trip to the West to prop up his sagging poll numbers. The trip was pretty grueling, taking him from Alaska, across British Columbia, to Seattle and eventually San Francisco. In Vancouver, BC he got exhausted while playing golf and his doctors prescribed digitalis and caffeine. (Just the thing for somebody with a bad heart!) On the evening of August 2 he seemed to be doing better, and was propped up in bed having a conversation with his wife. At 7:35 PM he croaked, right in the middle of the conversation. There was no warning. People with congestive heart failure sometimes do die this way.

Politically, Harding checked out at exactly the right time. Generally regarded by historians as being totally in over his head as President, Harding some arguable degree of personal honesty, but was extremely naïve and used very poor judgment especially in appointing friends to government jobs. As a result, his corrupt cronies looted the U.S. government for all it was worth. By summer 1923 the scandals were piling up: Teapot Dome (a smorgasbord of graft involving oil lands), fleecing the Veteran's Bureau, even a bootlegging ring run out of a house only blocks from the White House where Harding played poker and drank whiskey (remember, Prohibition was on). Harding's administration was perhaps the most corrupt in American history, at least until Donald Trump waddled onto the scene. Had he lived, Harding might have been forced to resign. His successor, Calvin Coolidge, was squeaky-clean, if a bit of a cold fish, so the scandals didn't stick to him.

And then there was the Nan Britton thing. Ostensibly a mild-mannered secretary from Marion, Ohio, Harding's hometown, in reality Ms. Britton was a creepy stalker who became obsessed with Harding at age 16 and evidently set her sights on becoming his lover. She was more than 40 years younger than he was. In the 1920s it was unclear exactly what happened between them, but she claimed she was successful, and that her daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, was Harding's, conceived in 1919. Britton also made the sensational claim that she banged President Harding in a broom closet in the White House. These accusations oozed out of a trashy kiss-and-tell book that Britton published in 1927 called The President's Daughter. For a long time it was not certain if Harding really did father her baby, as the Britton and Blaesing families declined to provide DNA evidence that would either prove or disprove the allegation. Britton died in 1991; Blaesing in 2005. Evidently the family changed its mind about the DNA. Ancestry.com proved Harding was Blaesing’s father in 2015, which proves at least the central thesis of her book was true.

Warren Harding had affairs, and with more women than just Nan Britton. For years he fooled around with a woman named Carrie Fulton Phillips, a pro-German sympathizer (in both World Wars) who successfully blackmailed the Republican Party with potential disclosure of their affair. Warren wrote naughty letters to Mrs. Phillips, which one historian was able to view in 1964, but whose public exposure is enjoined by a court order until 2024. As you can see, Harding seems to have stirred up trouble and suspicion in all quarters.

Florence Harding, Warren's long-suffering wife, went into immediate damage control mode when her husband died. Not only did she refuse permission for an autopsy to determine whether it was the crab meat or Warren's bum ticker that did him in, she promptly burned all of her husband's private and public papers. (Martha Washington did the same thing when George died). This naturally fueled speculation about what she was trying to hide, and some of Warren's cronies went so far as to accuse her of having poisoned him. She unfortunately missed those letters he wrote to Carrie Phillips. She may have been doing Warren's historical memory a favor. Teapot Dome, Nan Britton, the Veteran's thing and the house on K Street are only the Harding scandals we know about. Who knows what else Warren might have been involved in, wittingly or not?

Strangely, the country seems to have shrugged off the untimely death of President Harding. There was the requisite period of mourning, lying-in-state and the funeral train, to be sure, but there is no real sense of national trauma over Harding's death, certainly nothing even remotely comparable to the aftermath of the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy, or the natural-causes but still deeply traumatizing death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945. Harding was still reasonably popular in 1923, but Americans seem to have had no deep attachment to him. His successor, Calvin Coolidge, went to to accomplish remarkably little as President; his sense of timing, too, was exemplary, leaving office in early 1929 just in time to pass on the blame for the upcoming Great Depression to his successor, Herbert Hoover. 1920s Presidents were remarkably lucky or unlucky, depending on how you look at it. The strangest thing about the death of President Harding—crab meat and scandals aside—seems to be how quickly it faded in the public mind. Maybe America in 1923 didn't really need a President. Who knew?

☕ If you enjoy what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

💌 Feedback to share or want to say hello? Hit reply on this email or leave me a comment on Substack.