Stockfish Empire: The Hanseatic League in Bergen. [Part I]

The amazing story of how the Hansa people from Germany built a commercial and military empire...out of dried fish.

I spent this past week in Bergen, Norway for the occasion of a history conference (which was awesome, by the way). Although I first visited Bergen five years ago, it wasn't until this trip that I had a chance to really look around the city and take in its history, which is preserved to a unique and spectacular degree. I learned a great deal especially about Bergen's history as Norway's chief trade port and outlet to the rest of the world. The key part of this history was the presence of the Hanseatic League, which essentially ran Bergen as a company town for over 400 years, from the mid-14th to mid-18th centuries. This was a subject I knew nothing about before last week, but it's a fascinating one.

To understand who the Hansa were and what they were trying to do in Bergen, it's necessary to appreciate just what an odd place Norway was in the Middle Ages. A tiny country with few natural resources and almost no arable land, Norway was (and still is) basically a pile of inhospitable rocks jutting out of the sea. The idea of building a nation here was almost unthinkable. Earlier in the Middle Ages, the Vikings earned their keep by plundering richer coasts (including Ireland, which they were kicked out of in 1014). But the Norwegians did have one resource upon which much of their budding society depended: fish. But unlike other primitive fishing societies, who lived hand-to mouth or sea-to-frying pan as it were, the Norwegians figured out how to preserve their excess fish, which meant they had something they could make money from: an export product.

This export product came to be known as stockfish, and here's how it worked. In the rich cold waters around northern Norway, medieval fisherman would catch tons of fish, mainly cod, and haul them back to shore. Then immediately the fish would be gutted, leaving the tails on, and hung by those tails on a large A-shaped open wooden frame called a hjell. For months these fish would dry in the cold windy climate, preserved from rot or insects, until the fish became dry and stiff as boards. After that it was an easy matter to stack the fish in the hold of a ship and bring them to anyone who needed food, preferably for a price. It was up to the consumer to reclaim the fish into edible form; I'll explain how they did that in Part II of this article tomorrow.

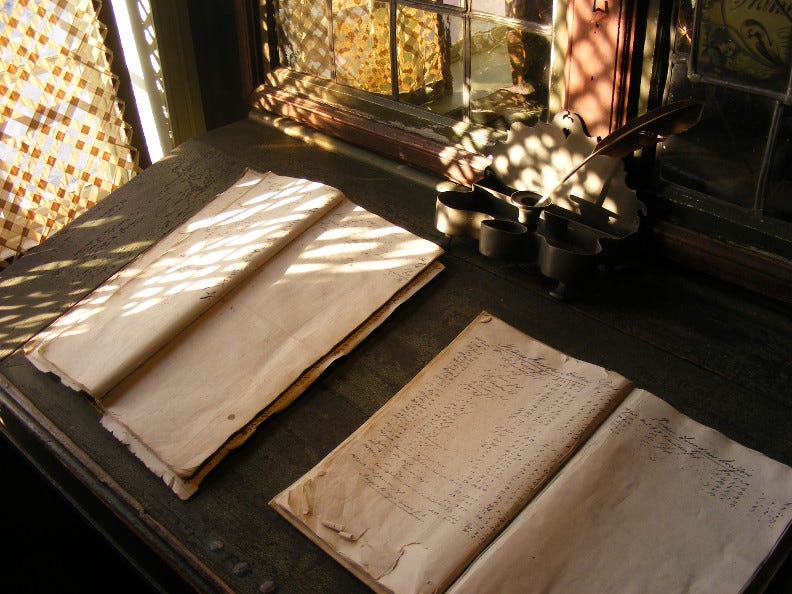

The drying of stockfish was a revolutionary technology when it was first practiced in Norway, sometime before 875 CE. It meant an income, above subsistence level, for fishermen and their communities, and could wire Norway into the network of trade that was then burgeoning across the Baltic and Northern Europe. Bergen was founded by Norwegian kings sometime in the 11th century mainly as a port for the trading of stockfish. The early wharves, which would eventually become the Hanseatic kontor, were built on the small waterfront shortly after this time. Their timbers can still be seen today in the archaeological section of the Cultural Museum in Bergen.

At about the same time, a guild, or Hansa, of seafaring traders was getting started in the North German town of Lübeck. (Horror fans may recognize Lübeck as the place where Nosferatu was filmed in the 1920s). The Hansa sought to band together, especially to defend themselves against pirates, and worked with each other in increasingly exclusive networks of trade which expanded throughout the 13th century. By 1300 the Hansa traders were very active in numerous ports whose names we recognize today, such as Hamburg, Bremen, Cologne and Groningen. Eventually they adopted a modus operandi. In these cities they would establish a kontor, a sort of import/export office. Hansa merchants would buy local goods and sell them to other Hanseatic cities. The kontors became cities unto themselves, with their own officials, dormitories and laws that applied only to them. The Hansa, who spoke German and practiced German customs, manned these posts entirely with their own people.

By the early 14th century the Hansa had its eyes on Bergen and its lucrative stockfish trade. In 1343 they succeeded in establishing a trading post on the water there. Now an influx of Germans appeared in Bergen, and with it a lot of economic opportunity for the local Norwegians. The Hansa would buy stockfish from local traders, load it onto Hanseatic ships and transport it west. Local people and businesses benefited from this trade, though perhaps not as much as one might expect given the fact the Hansa tried to keep most of their basic functions in the hands of their own people, who took oaths to the League and essentially worked for them for life. In a Europe where most other people were serfs under feudalism, this wasn't a bad lifestyle.

These early years of Hanseatic presence turned out to be tragic for Bergen. Just a few years after the Hansa arrived, in 1349, rats on board a British ship brought the Black Death to Norway. Indeed the extensive trade networks of the Hanseatic League were instrumental in spreading the deadly plague throughout Europe. The disaster wiped out a third of Europe's population and left the continent in a state of physical, demographic and religious ruin not unlike the aftermath of a nuclear war. Bergen and its Hanseatic Kontor survived, only to face more hardship. In 1393 a guild of privateers called the Vitalians—also known as the Victual Brothers—sailed into Bergen to sack and pillage it. This guild of pirates was ironically once in the employ of the Hanseatic League, then at war with Holland, but the lure of rich plunder caused the Vitalians to pink-slip their former employers before hurling projectiles at their cities. Bergen's wooden kontor was burned to the waterline and the Vitalians made off with shiploads of treasure, presumably including stockfish that they could sell in other European countries. The Vitalians returned twice more, in 1395 and 1428, treating Bergen like a virtual ATM machine that was convenient to raid whenever the privateers needed money.

Despite these setbacks, however, as a whole the Hanseatic League rebounded and by the early 15th century was at the height of its power. Norway was not yet a nation in the sense we understand modern nationhood, and an argument can be made that the domestic production of northern Norway—that being stockfish—was almost totally controlled by foreigners. But the Hanseatic involvement in Bergen at least began forging the building blocks from which the Norwegian nation would eventually, centuries later, be made.

In Part II of this article, I will trace the history of the Hansa in Bergen from the 14th century until the stockfish trade was taken over by Norwegians in the 18th century--it's a fascinating story! Stay tuned!

Originally published November 25, 2014.

☕ If you enjoy what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

💌 Feedback to share or want to say hello? Hit reply on this email or leave me a comment on Substack.