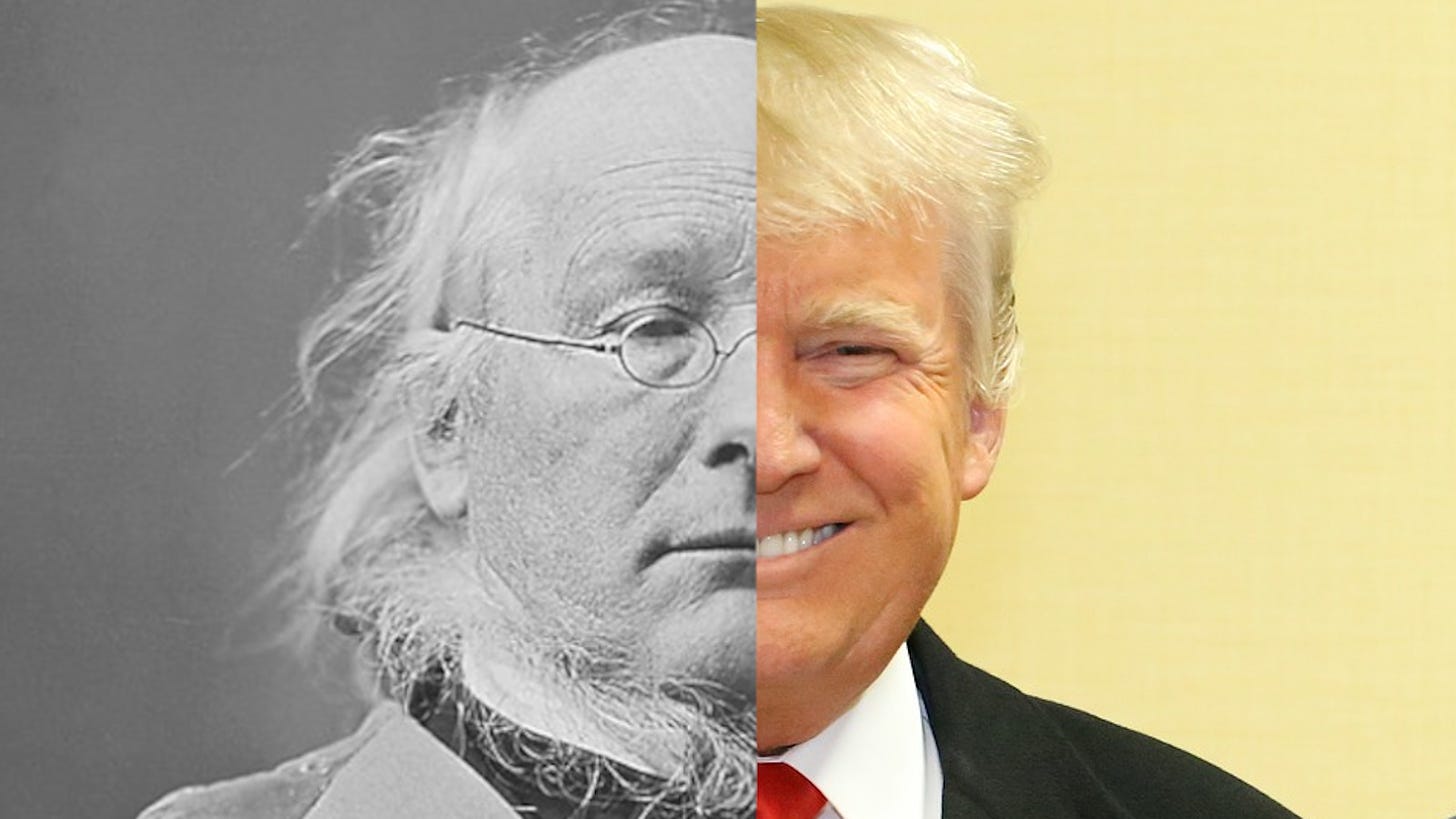

The pain of losing: A tale of two candidates.

In 1872, Horace Greeley was institutionalized after losing a Presidential election. Donald Trump wasn't, but perhaps he should have been.

On November 24, 1872, just 19 days after the U.S. Presidential election of that year, New York newspaper publisher Horace Greeley went to the privately-owned convalescent home and hospital of one Dr. George S. Choate at Pleasantville, New York. Greeley was seriously unwell, apparently with mental as well as physical illnesses. Confined to his bed, Greeley’s condition worsened rapidly. He died on November 29, age 61. The cause of his death wasn’t entirely certain but it appears to have been a complicated web of physical and mental conditions. He was, at the time, suffering from severe grief. Greeley’s wife, herself also ill for a long time, died on October 30. Greeley was the Democratic and “Liberal Republican” nominee for President of the United States. A week after his wife’s death and three weeks before his own, Greeley lost the election badly to incumbent Republican Ulysses S. Grant.

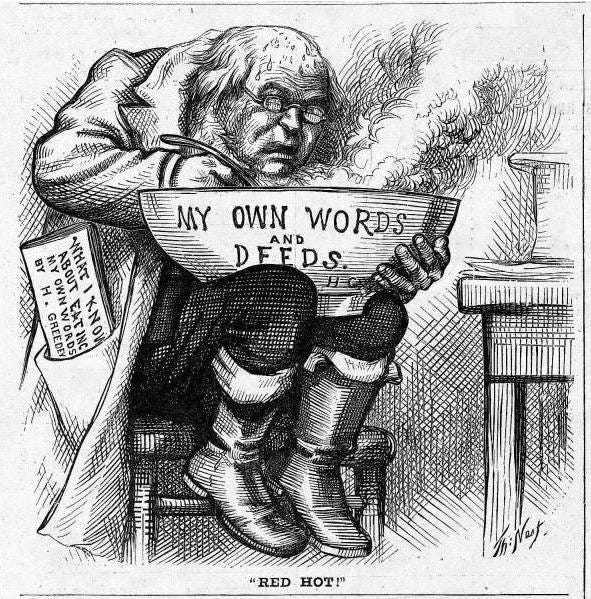

A legend, born mostly out of historical shorthand, has grown up around Greeley’s death: that he was crushed so decisively by Grant in the election that he went crazy and immediately died. Couched in these terms the legend bears more than a hint of stigmatizing mental illness, but it’s a common enough idea. Choate House, where Greeley died, was known as a “sanitarium,” a term which had a much broader meaning in the 19th century than it did later. Although the term is archaic now, for much of the 20th century “sanitarium” was popularly synonymous with “mental hospital,” and it is true that Greeley’s problems just before his death were at least partially mental in nature. But the legend’s casual connection of his loss in the 1872 election to his mental illness obscures much. Greeley was much more affected by his wife’s death than the result of the election, which was not a surprise. As early as October 14, the results of New York state elections (which were in those days not held contemporaneously with federal ones) showed he would lose. In fact Greeley wrote on that date:

“You must not take our reverses to heart. I may soon have to shed some tears for my wife, who seems to be sinking at last, but I shall not give one to any possible result of the political canvass.”

One hundred and forty-eight years later, another candidate, Donald J. Trump, also from New York, lost the 2020 Presidential election. Trump’s reaction to losing the election is considerably different than Greeley’s, and also somewhat more difficult to parse. According to the recent book I Alone Can Fix It: Donald J. Trump’s Catastrophic Final Year by Carol Leonnig & Philip Rucker, there seems to have been some glimmer in Trump’s mind, in the days following the election, that he had lost. On November 13, 2020, during a press conference in which he rejected out of hand the possibility of the federal government declaring a lockdown as a result of rising coronavirus deaths, Trump said, “Hopefully whatever happens in the future, who knows which administration it will be, I guess time will tell.”

By early December, however, it seems that whatever self-awareness Trump might have had about losing the election was gone. Since that time he has, without exception, loudly and consistently maintained that he actually won. If you look at his actions and his public statements since that time, it’s hard to come to any other conclusion than the obvious one: he really, honestly believes that he won—something that is manifestly and obviously untrue, in other words, a delusion. It’s astonishing that the press and pundit class hasn’t highlighted this more consistently. It seems to be an unspoken subtext of most news writing that Trump can’t really mean what he says, that he must be keeping up appearances for political purposes, or perhaps to grift his millions of gullible supporters. But it’s right out there in the open. Trump believes he won the 2020 election. He is delusional. He’s mentally ill.

Presidential medical historian Dr. John Sotos, author of The Physical Lincoln, maintains an extensive database on Presidential health throughout history. He’s not a psychologist but he’s relied heavily on the work of Dr. Mary Trump, the former President’s niece, who is, and who has diagnosed her uncle with severe personality disorders. Here’s what Dr. Sotos has to say about Trump’s election delusions:

If he has a genuine belief that he won the 2020 election, that is a delusion, defined by psychiatrists as "a fixed idea at variance with reality, unamenable to change, with the exception of religion." Delusions may occur as a symptom of severe personality disorders. But if his belief about winning the election is not genuine, and is instead part of a cynical ploy to manipulate the public and retain power, then that, too, is compatible with his antisocial personality disorder -- in fact, it is the essence of his disease.

The most fascinating—and saddest—part of I Alone Can Fix It is its epilogue, in which the two authors, Leonnig & Rucker, visited Trump at Mar-a-Lago in early 2021, after he left the White House. You would think, as fixated as he is on positive publicity and distrustful as he is of the press, that Trump wouldn’t give these reporters the time of day. In fact, according to them, he was with them for over two hours. And he had essentially one message. From the book:

Trump was fixated on his loss in 2020, returning to this wound repeatedly throughout the interview…Trump seemed determined as well to convince us that he actually had won, and handily, had it not been for the many people who had wronged him—the “evil people” who conspired to deny him his rightful second term.

“The greatest fraud ever perpetrated in this country was this last election,” Trump said. “It was rigged and it was stolen. It was both. It was a combination, and [Attorney General] Bill Barr didn’t do anything about it.”

That Trump was deranged and delusional at least at the end of his term is scarcely arguable. Nancy Pelosi knew it; she used those words (deranged and delusional) when she contacted various White House staff members and military personnel to ensure that, if Trump ordered a nuclear strike, they would disobey him. She also counseled for his immediate removal via the 25th Amendment, a procedure—supposedly—put in place for just this event, where a President is too mentally or physically ill to carry out the job. No one who could have acted on the 25th Amendment seems to have seriously considered it.

That the 25th Amendment wasn’t invoked is a problem, but a separate one from the thesis of this essay, which is to contrast the mental illnesses of Horace Greeley in 1872 and Donald Trump in 2021. Greeley is somewhat infamous for having “gone crazy” and died, shortly after the election, and his loss is invariably mentioned in connection with the circumstances of his insanity and death.

Yet there’s serious question about whether the election result had anything to do with Greeley’s final decline or not. Some of his friends claimed his mental state had been deteriorating for years and he was already on the brink by 1872. Even if not, he’d been married to his wife, Mary, for 36 years. Obviously her death would have crushed him. Though not exactly a reluctant candidate—he was famous in America in the early 1870s for railing against the corruption of the Grant administration—politics was not his chosen profession. He became an influencer via his stewardship of the New York Tribune. He wasn’t even a Democrat. The party that nominated him in 1872 was the short-lived Liberal Republican party, a splinter faction of Grant’s Republicans who favored a different candidate. Democrats, demoralized by the Civil War, almost sat the election out. They endorsed Greeley but he was not one of theirs and not nominated at their own convention. It’s hard to argue that being President of the United States was his life’s ambition, such that he would go insane and die if it was thwarted. After decades on the national stage, by 1872 Greeley was an old, sick, tired man. We can’t know what was in his mind, but I doubt, as he lay dying in a bedroom of Choate House on a raw November afternoon, that disappointment at not being President was foremost on it.

Trump, on the other hand, can seem to think about little else. And it’s not because he has such grandiose plans for a second term as President: it’s purely psychological, because the idea of being a loser, rejected by the American people, is incapable of existing in his fevered mind. He literally believes he’s the greatest President of all time. As he told the authors of I Alone Can Fix It in early 2021:

“I think it would be hard if George Washington came back from the dead and he chose Abraham Lincoln as his vice president, I think it would have been very hard for them to beat me.”

It’s difficult, given the horrendous damage he did to our republic, to pity Donald J. Trump. Thinking rationally about him, it’s clear that he, like Horace Greeley in 1872, is an old, sick, tired man, addled by mental illness and physically terribly unhealthy. (Look at the shocking physical deterioration in Trump from 2017 to 2021). Maybe it’s the weight of time or the absence of partisan tribalism that makes it so much easier to think of Greeley with sadness and charity. It still amazes me, though, that fewer people in the chattering class in the U.S. today are speaking frankly about Trump’s mental condition. Does he not need care and treatment, as Greeley clearly did? Shouldn’t he be checked into a “sanitarium” until he recovers, if ever? Why is this taboo to talk about? I don’t have an answer to that question.

Incidentally, Greeley’s death, coming so soon after the 1872 election, occurred before the electoral votes were counted, the only instance in American history where a Presidential candidate died during the electoral process. It was a minor constitutional crisis—minor because it made no difference to the outcome, which was that Grant would continue in the White House for another four years. There’s an interesting story about how this was resolved, but it’s not for this article. Greeley was buried on December 4, 1872 and his grave still stands today. He was honestly mourned by tens of thousands of New Yorkers and millions of ordinary Americans. They did not want him as President, but they seem to have liked him well enough.

The photo of Choate House is by Wikimedia Commons user Ɱ used under Creative Commons 4.0 license. Header images are in the public domain. I am uncertain of the copyright status of the other images but believe fair use applies.

☕ If you enjoy what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

💌 Feedback to share or want to say hello? Hit reply on this email or leave me a comment on Substack.