The Tools Cult: The History of the Amway Motivational Scam. (Part 1 of 3)

This is the incredible story of how a tiny group of audacious men built one of the biggest grifts in American history--with far-reaching consequences.

This series of articles is adapted from my in-depth video on the subject, available on my YouTube channel, embedded above. Additional chapters will be released on the next two successive days.

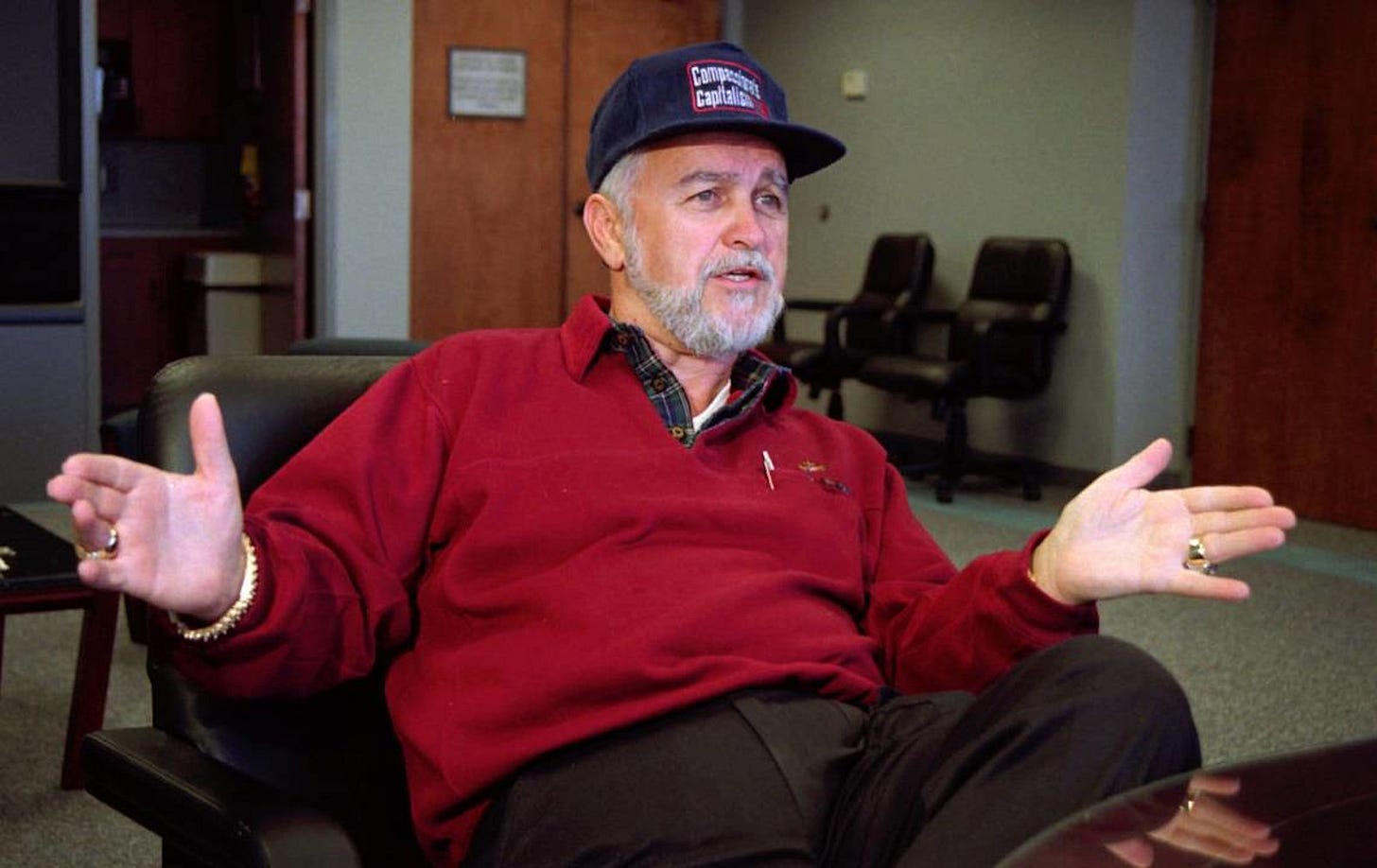

This is the true story of one of the most bizarre and influential organizations in recent American history, the story of the men who built it—principally a man named Dexter Yager—and the story of this organization’s epic battle against the multilevel marketing corporation that it both relied upon for its existence, and which was also its mortal enemy at the same time. This organization, which doesn’t even have an official name, was and is a business that generated hundreds of billions of dollars across six decades, enriched a tiny number of its top kingpins to levels of virtually unimaginable wealth, and granted those men access to the most exclusive corridors of power. To hear the stories of some who were in it, this organization also stole people’s souls, drove them into poverty, and wrecked the lives of many more.

This is the story of the Amway tools cult: a shadowy organization, begun in the early 1970s, which a dozen years later effectively hijacked the biggest and most profitable multilevel marketing company in history. A lot continues to be written about multilevel marketing, its inherently deceptive nature and even its connections to political corruption in the United States. But this particular story isn’t often told as a story unto itself—meaning, it gets mentioned on the fringes of discussion of the history of Amway and multilevel marketing in general, but to my knowledge no one has ever sought to chronicle its history and evaluate its significance. It is mainly the story of the origin of this mysterious business and its epic clash with the Amway corporation itself which climaxed in 1982 and 1983.

I am not an “MLM survivor,” and this is not a first-person MLM horror story as those are often told, particularly on social media, by people who have been victimized by these businesses. Instead, this is a look at some of the inner workings of the American economy and political system in the age of late capitalism. It is perhaps a symptom of the dysfunction of the American system, rotted with greed, gorged on fossil fuels and siloed behind walls of impenetrable political corruption, mainly by Christian evangelical conservatives. Amway has long professed to embody the “American dream.” You may come to appreciate, as this story unfolds, how much of the “American dream” is impossible to distinguish from grift.

Amway, 1978

Imagine it’s sometime in the 1970s. Vietnam is over, Jimmy Carter is in the White House, Archie Bunker is on TV, bell bottoms and polyester are all the rage, and gas is in short supply. A friend, most likely a white middle-class man, comes to you and tells you about a “great business opportunity” and how he’d love to get together with you to explain it to you.

You get in your AMC Pacer and drive to the meeting at your friend’s house. Your friend produces butcher paper and some markers, and draws a bunch of circles on them, explaining how you can make a lot of money—not by selling SA-8, which is soap, or LOC, which is also soap, but by sponsoring others to sell soap, and you take a cut of everything they make. He doesn’t even mention until the end of the presentation that it’s Amway, and even then the involvement of Amway seems pretty minor—they’re just the corporation that manufactures the soap.

What I just described is the classic Amway entry experience for tens of thousands of people, not just in the 1970s but down to the present day. It’s called “showing the plan,” or in slang terms “drawing circles,” and a story like this is the beginning of nearly every Amway story.1

Amway—a portmanteau of the words American Way, used in somewhat Orwellian fashion here—was a company founded in 1959 by two salesmen, Richard DeVos and Jay Van Andel, who were formerly salesmen in another organization, Nutrilite, generally regarded as the first multilevel marketing company. Both DeVos and Van Andel were conservative, evangelical Calvinists, and their fundamentalist worldview shaped the entire Amway universe.

The tangled history of the invention of multilevel marketing, Nutrilite and the founding of Amway is documented in the excellent book Ponzinomics: The Untold Story of Multi-level Marketing by Robert FitzPatrick, the leading academic who studies the MLM phenomenon and how it relates to American business history and culture.2 This book is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand this segment of the economy and the inner workings of the entire MLM system.

Although Amway has changed a little bit since the 1970s and 1980s—the key period I’m covering in this video—its essence is today basically the same as it was then.

If you accept your friend’s invitation and join Amway, what you’ve just done is to become a “distributor.” You’ve just joined a “line of sponsorship.” Your friend is your upline. You are in his downline, which means that you order all of your Amway products—soap, mostly—from him. All your products: the stuff you buy for yourself, and more importantly, the stuff you buy to sell to the people you recruit to sell Amway soap, or your downline.

In the 1970s, once a week you would get in your AMC Gremlin and drive to your friend’s house to pick up the boxes of soap—and some other stuff, which becomes important later—anyway, you pick up your stuff at his house, and then presumably you set up a meeting for your downline to drive to your house in their Ford Maverick or woody station wagon to pick up their stuff from you.

But here’s the rub: how many people do you know, realistically, who are going to sign up to buy soap from you? Or food bars, or whatever else Amway sells? Chances are pretty good that, if you ever succeed at recruiting anyone else into “The Business”—which is monolithically what Amway distributors call it—you’ll quickly run out of people to hustle. So, if you want to stay in, it will just be you, your AMC Gremlin, and the couple boxes of soap that you bought from your friend.

In 1980, the Wisconsin Attorney General crunched the numbers of the top 1% of Amway distributors in that state to see what they really made. The result was shocking. Though most of those 1% posted a profit on paper, with operating costs deducted, almost every single one of them lost money on a net basis—with the average loss penciling out to $900 dollars.3 This was the top one percent of all distributors in Wisconsin. Thus, an infinitesimal sliver of distributors actually make a profit. Your odds of winning at gambling in a casino are mathematically higher than making money at Amway.

These are the basics of how Amway distributorships work. There are legions of documents, blogs, YouTube videos and other content to demonstrate this, and this is indeed the central focus of a majority of the anti-MLM community when they talk about Amway. That analysis is correct; chances are virtually certain that you will lose money becoming an Amway distributor, or in any MLM, really. But the real story is deeper than that—it’s the tools cult, which sort of hides behind the public face of the Amway experience.

The Tools Cult

So what is the “tools” business? And why is it a cult? You might think “tools” refers to hammers or wrenches or rakes or something. Not in this context.

Recall our starting example. Back in the bell-bottom, Jimmy Carter 1970s, you’ve just been hustled by your friend to become an Amway distributor, and after he’s tantalized you with the illusory promises of all the wealth you’ll enjoy by recruiting people to sell soap, you load the Amway starter pack into the back of your AMC Gremlin.

That box contains soap, obviously. But it also contains something else.

In the 1970s, a newly-recruited distributor would find in that box a couple of books, such as The Possible Dream by Charles Paul Conn, The Magic of Thinking Big by David J. Schwartz, and Don’t Let Anybody Steal Your Dream, by a fellow named Dexter Yager. Also included would be a couple of cassette tapes.4 Pop one into your cassette player on the drive home from your friend’s house—assuming your AMC Gremlin is posh enough to have a cassette player—and out of the speakers will come a man’s voice talking about how you have to seize your dreams and envision success in order to make it.

Those are the tools: tapes, books, and also live seminars and rallies, all of them of a motivational nature. Later, as the tools system became more sophisticated, tools would eventually include things like a special voice mail system called Amvox, but as our paradigm case is in the ‘70s, let’s stick with tapes, books, seminars and rallies. In Amway parlance they’re known sometimes as “BSMs,” or Business Support Materials.5

What the tools are supposed to do is to help Amway distributors recruit people to sell soap, and also other trinkets the Amway corporation manufactures, like food bars, energy drinks and other incidental merchandise. But the big deal is to recruit. Show the plan. Draw circles. That’s the lifeblood of the Amway business, and that’s the definition of multilevel marketing. The tools are supposed to motivate you to succeed.

Just to be clear: your buddy who got you into Amway will never require you to buy the tapes. But he might say something like this: “I want to help you in every way I can. It would be a disservice not to sell you the tapes and books and tickets. Hey, you’ll be moving dozens of these down through your organization in a few months.”6

In fact, purchase of the tapes and books isn’t really optional. The fiction that it is, is a fig leaf to confer a veneer of legality. Even the Amway corporation itself documented the pressure put on distributors to buy tools. If they didn’t, their uplines would refuse to associate with them.7

In the 1980s and into the 1990s, the tapes cost $5-$6 apiece and were often presold to Amway distributors by an arrangement known as the “standing order.” This meant that the distributor agreed to buy a tape, usually once a week, every week, regardless of what it was, until the order was canceled.8

In fact it was even more egregious than that. One of the kingpins of the tools business, Doug Wead, who features prominently in the later part of this story, said that the wife of a fellow kingpin, Betty Jo Renfro, once upbraided him for talking at an Amway rally about the “tape of the week.” According to Wead, Renfro said to him: “Don’t you ever talk about tape of the week to our group. We move more than one tape a week. We have the tape of the day or the tape of the hour.”9

Five dollars in 1980 is about $17 in today’s money. The markup on these tapes was colossal. They cost about 60 cents apiece to make.10 Tapes were not just sold to distributors through the usual process of distributing products to their downlines. They were also sold at rallies and seminars themselves. Kingpins would set up tables at the entrances to these rallies—typically in large hotel ballrooms, or, in some cases, stadiums and sports venues—and offer all the latest tapes at a gigantic markup. Much of the time they sold out, from distributors attending the rallies who just had to have that extra dose of motivation. Table sales of tapes and books at Amway rallies could yield the kingpins as much as $10,000 a night—in cash.11 That’s big, big money. In fact, it’s far more money than the pittance that distributors are making selling soap to each other.

Thus, the Amway universe really consists of two businesses. The first business is Amway itself, which is dependent on “drawing circles” and “showing the plan” to gain a never-ending stream of recruits, who buy products like LOC (soap) and SA-8 (also soap), and those profits inure to the benefit of the Amway corporation, the manufacturer of the soap. The second business is the sale of tools to Amway distributors. Although they’re related, they’re separate businesses. The ownership, control and profits of the Amway corporation are within the hands of a different group of people than the ownership, control and profits of the tool businesses—even if the people from whom each of them makes their profits are generally the same people.

Now, in 2022, thanks largely to the anti-MLM movement, most people know that multilevel marketing operations are functionally the same as pyramid schemes. Amway takes care to stress that, according to a Federal Trade Commission ruling from 1979, it is not a pyramid scheme, but the difference between what the FTC defined as a “pyramid scheme” in 1979, and whatever Amway is, is an extremely fine and technical one. The distinction is based on whether any of the products are actually sold to people outside the organization. In fact it’s a rule, set by this 1979 decision, that Amway has to abide by. In reality only a tiny proportion of products that Amway manufactures ever wind up in the hands of people outside the Amway organizations. This is why people argue—convincingly, in my view—that it is functionally the same as a pyramid scheme.

Here is one way to envision these businesses and their relationship. Imagine two pyramids, not exactly one nested inside each other, but with significant overlap. One pyramid, representing the Amway MLM business, is much smaller than the other. The second pyramid, much larger, is the tools cult. In visual representation it’s semi-transparent because it gets noticed a lot less, or, from a distance, people assume it’s a reflection of the smaller pyramid.

Although these two pyramids are symbiotic, and in fact neither can exist without the other, they are separate, under separate ownership and separate leadership. The relationship between them is historically acrimonious—they don’t like each other very much but each recognizes the other as a necessary evil.

Most discussion of Amway in the anti-MLM space focuses on the smaller, more visible pyramid—the one that relies on recruiting and makes most of its money selling soap to Amway distributors. The major questions about how much money a typical Amway distributor makes, whether the promises of income are plausible, and that sort of thing, focuses on this smaller pyramid. The 1979 FTC ruling, which Amway has for decades trumpeted as the seal of legality and approval, pertains solely to the smaller pyramid.

Yet when people talk about Amway being a “cult” or “cult-like,” what they’re really talking about is the larger pyramid—the tools cult. Here’s where most of the money is and a lot of the abuses occur. It’s best to describe the legality of this as “untested.” The tools business has not been declared legal by the FTC (nor has it been declared illegal). Even a lot of anti-MLM people assume these pyramids are congruous and that Amway is a monolithic phenomenon. They’re not, and it isn’t.

So what is the tools business really selling? Surprisingly little, to be honest. If you’ve heard one of these tapes, you’ve basically heard them all. A lot of motivational talk about envisioning your dreams, and especially fantasizing about how rich you will eventually become by being an Amway distributor. Furthermore, these tapes are often made by simply tape-recording motivational speeches given from the stage at rallies.

The rallies themselves were bizarre experiences, rife with pageantry and populist hysteria, at which Amway stars—the Diamonds, the tools kingpins, mostly, especially Dexter Yager—would be feted like conquering Roman emperors, or rock stars. One especially fervent Yager rally in 1980 ended with Amway distributors spilling out into the streets at 3:00 in the morning, chanting in unison, “Five and six! Nights a week! Five and six! Nights a week!”12 That referred to the number of nights they intend to go out and “draw circles” for Amway.

The term Diamond has particular importance in this bizarro universe. There’s a complex hierarchy of pin levels in Amway, all named after various jewels. Supposedly, as one moves up in the organization and quote-unquote “go direct,” meaning you’re ordering enough soap that you don’t have to drive over to your friend’s house in your AMC Gremlin but can order it directly from Amway, you might then become a Pearl, or a Ruby, or an Emerald, or, the brass ring, Diamond. It doesn’t matter the exact order of the levels, but Diamond was the ultimate—at least at first, before Amway had to invent higher levels as the kingpins’ businesses grew, similar to the way the Church of Scientology invented higher “Operating Thetan” levels as its original high achievers moved “up the bridge.” Amway distributors speak in glowing terms of “going Diamond,” which is a euphemism for financial success. “When are you going Diamond?” As if it’s a foregone conclusion—a matter of time—which the motivational psychobabble of the tools constantly reinforced. Indeed, the tools and rallies contained precious little advice on how to sell soap. Usually they talk in vague terms about how many material possessions you’ll have—Cadillacs, boats, mansions—once you “go Diamond.”

But how much “motivation” does a soap salesperson really need? It would be one thing if the tools were actually sales advice or training. But they’re not. They’re just “what color Cadillac do you want?”

Despite their lack of content, the tools proved highly addictive. Numerous apostates from the tools cult have reported, year after year, decade after decade, that constant exposure to tapes and rallies produced a behavior-altering affect that changed their thinking, and, in many cases, emptied it.13 Listening to tapes recorded at rallies was intended to reproduce the euphoric effect of attending those rallies. Whenever your faith in the Amway dream falters, listen to a tape and get roped back into the fold. Soon enough you’ll be back running through the streets at 3AM chanting, “Five and six! Nights a week!”

This is why people refer to Amway as a cult. They’re not referring to the Amway corporation, which, as you recall, sells soap. They’re referring to the tools business, its closed and coercive nature, and its behavior-altering effects. The very vapidity and lack of substance in the tools themselves is a dead giveaway that they’re not, and never were, business support materials. It’s not about helping Amway distributors succeed at selling soap—which over 99% of them won’t anyway, regardless of circumstances. The tools themselves are a business, and those who consume them with increasing devotion, not merely its followers, but its customers.

Britt & Yager Found the Tools Cult

In 1964, the Beatles were taking America by storm. Racial segregation was banned in the United States—in theory. Lyndon Johnson was running for a full term as President, and Julie Andrews was flying across movie screens on her umbrella. And also that year, a man named Dexter Yager became one of the early distributors in Amway, a company which, at that point, was only five years old.

As a historian, finding the true story of Dexter Yager’s life reminds me of nothing so much as researching the biographies of medieval saints. So many layers of hagiography, much of it spun by Yager himself, surround his life story that it’s almost impossible to separate fact from fiction. What we do know is that he was born in 1939 in the small town of Rome, New York—which 60 years later would become the infamous setting of Woodstock ‘99—but long before that, the Yager family lived there, and they were evidently poor. Much of the hagiography he generated about himself in later life stressed his poverty. It also emphasized the narrative that he was some sort of “born salesman.” He claimed that while he was in the sixth grade he sold bottles of soda to construction workers for a dime apiece, then raised his profits by buying the Coke wholesale.14

Personally, I doubt this narrative; I suppose it could have happened, but this is a classic example of the sort of “born salesman” origin story that was extremely popular in the culture of salesmen in the mid-20th century, especially the 1960s. Being able to say you were a successful salesman as a kid, especially for someone who became rich in a sales profession later in life, was the entry ticket to the kind of glowing “Horatio Alger story” that salespeople in this era wanted to emulate.15

Dexter Yager’s life story as he often told it was a tale of quasi-religious redemption by the light of the Amway miracle. Supposedly he sold tools (the real kind, from Sears), he was a car salesman, and a beer salesman (West End Brewery). Also (according to his own story) he was a heavy drinker. What Yager did not emphasize in his own hagiography was that, after he became an Amway salesman in 1964, he didn’t make much money at it—despite “going direct” very quickly, and despite him saying, quote, “I ate, slept and breathed the business seven days a week.”16 We know Yager wasn’t making money at Amway because within three years he was applying for other jobs.17 This is actually a pretty damning fact. This was only a few years after the founding of Amway.

How can one of the earliest adopters of Amway not make money at it? This is evidence the business model was already financially exhausted within a couple of years. There just wasn’t enough money in (quote) “the plan” to sustain people with full-time incomes—something that was still the case in 1983 when one of the tools kingpins complained about it in a remark caught on tape.

Then, sometime in the mid-1960s—probably 1966—someone (possibly Fred Hansen, apparently one of the original Amway distributors sponsored in the 1950s by Rich DeVos) loaned Yager a copy of Earl Nightingale’s 1956 spoken word record The Strangest Secret. This was the earliest “motivational tape” and it was a big fad in the 1960s. Nightingale was himself inspired by Napoleon Hill, who wrote Think and Grow Rich in 1937 (which would later be at the top of the classic Amway reading list). Hill was a con man with a long string of failed businesses, but he was riding the first wave of motivation/self help that came out of the 1930s—the same cultural phenomenon that gave us Dale Carnegie’s manipulative classic How to Win Friends and Influence People, which inspired, among others, Charles Manson. Another follower of Napoleon Hill was conservative evangelical preacher Norman Vincent Peale—in whose New York congregation was the Trump family. Yes, that Trump.18

Fall 1966. The United States was now deeply and directly involved in the Vietnam War. Star Trek premiered on NBC television. And at this time, Yager sponsored Tony Renard into Amway. Renard also had an interest in Earl Nightingale tapes. Renard then bought a secondhand tape recorder from Yager and begins duplicating motivational tapes.19 Doug Wead, who is the source for this story—albeit a somewhat unreliable source—would later call this “the best investment of the 1960s” and he was probably right.

By the late 1960s, motivational tapes began moving through Yager’s downlines. At first they were not a profit center. However, similar things were happening with other proto-MLMs—both Holiday Magic and Koscot Interplanetary, two early multilevel marketing scams, were also beginning to develop motivational divisions. The Amway corporation itself also had a small operation of motivational materials, but Amway itself was never a large player in the motivational tools sphere.

In 1969, Dexter Yager and family—his wife Birdie and four kids, eventually seven—moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, probably so Yager could be closer to important people in his downline. This put Yager in the right place at the right time to sponsor the next major player in the tools saga, William “Billy” Britt, who joined Amway in 1970. If you think the truth of Yager’s life is hard to pin down, Britt is even more of a black box, with virtually every mention of him in the historical record surrounded by cocoons of salesman and motivational hagiography.

What we do know about Britt is that he served in the Army in the Korean War vet and was a minor official in a few municipal governments in the Charlotte, NC area.20 Britt was sponsored into Amway by Dominick Coniguliaro, whose sponsor was Dexter Yager.21 (These upline/downline relationships are similar to family genealogies—another reason why Amway organizations resemble the structure of the Mafia).

Sometime after 1970, but probably not long after, the true origin of the tools business took place. Here are the exact words of the source we have for this, which was written by Doug Wead—who I’ll profile in a future segment.

“Then, a bright, young man, who will remain nameless, changed everything. He sat across from Dexter Yager and Bill Britt in the coffee shop of the Fontainebleau Hotel and told Yager that for a $50,000 investment he could buy the latest machinery and set up his own tape duplicating company. Dexter turned him down. Britt said, “I’ll do it.” And so the modern networking tape business was born.” 22

Who was the “bright young man who will remain nameless?” We don’t know. It could theoretically have been Wead himself, as he did talk about himself in this way sometimes; but Wead was only 24 in 1970 and by most accounts did not meet Dexter Yager until later in the 1970s. But whoever it was left an indelible mark on the Amway universe. The revelation itself is important: by 1970 or 1971, someone had noticed there was enough profit potential in the tools to offer significant return on a $50,000 investment. ($50,000 in 1970 was about $371,000 in today’s money). This was also the time cassette tapes were becoming ubiquitous; the saturation of a new technology is often a vector for marketing schemes that explore and pioneer various new ways to make money with that technology. Such was certainly true of Amway’s tapes.

Britt began manufacturing tapes on a mass basis, and Yager began distributing them throughout his downlines. Britt seems to have offered Yager a sweetheart deal on tapes at wholesale. Within a few short years, they both became very rich, and highly influential in the Amway organization. For at least this small group of men—principally Bill Britt, Dexter Yager, and the nameless young man—the central problem of the Amway business, which was that it was largely impossible to make any real money at it, had been solved. Based on the work of self-help grifters like Dale Carnegie, Napoleon Hill, Norman Vincent Peale and Earle Nightingale, these men discovered an entirely new and fabulously lucrative income stream to replace the largely illusory income they should have been earning by recruiting people to sell Amway soap.

Was this discovery an accident? We can’t know, because there are so few primary sources. But it may not have come entirely out of left field. The Amway tools cult as it developed was unique, but it bears some similarities to other motivational organizations and ideologies that were developing around this same time—organizations that have also been likened to cults. That’s where we turn next.

In the next installment: the bizarre histories of Koscot Interplanetary and Holiday Magic; Doug Wead, the mysterious man who may have been at the center of the tools business; and Amway declares war on the tools cult, or vice-versa.

Sources

1Stephen Butterfield, Amway: The Cult of Free Enterprise (Boston: South End Press, 1985), 46-49.

2Robert L. FitzPatrick, Ponzinomics: The Untold Story of Multi-Level Marketing (Charlotte, NC: FitzPatrick Management Inc., 2020).

3Jon M. Taylor, The Case For (and Against) Multi-Level Marketing, Consumer Awareness Institute, p.2 (https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_comments/trade-regulation-rule-disclosure-requirements-and-prohibitions-concerning-business-opportunities-ftc.r511993-00008%C2%A0/00008-57281.pdf).

4Butterfield, p. 51.

5Ruth Carter, Amway Motivational Organizations: Behind the Smoke and Mirrors (Winter Park, Florida: Backstreet Publications, 1999), 30-31.

6Butterfield, p. 51.

7Rich DeVos, “Directly Speaking” [audio tape], January 1983, transcription: https://web.archive.org/web/20060422014637/http://www.amquix.info/amway_directly_speaking.html.

8Eric Scheibeler, Merchants of Deception (Self-Published, 2004), 39 (https://archive.org/details/MerchantsOfDeception/mode/1up).

9Doug Wead, “How the Amway Tool Business Began,” Doug Wead Blog, April 14, 2014 (https://dougwead.wordpress.com/2009/04/14/amway-and-the-tools/).

10Carter, p. 73.

11Scheibeler, 290-91.

12Butterfield, p. 174.

13See, e.g., Scheibeler, p. 179; Butterfield, p. 179-85; Carter p. 43-45.

14Jim Morrill & Nancy Stancill, “Amway, The Yager Way,” The Charlotte Observer, March 19, 1995 (http://www.ex-cult.org/Groups/Amway/dexter-yager-1.txt).

15See, e.g., John S. Wright, “Sol Polk,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Apr., 1966), pp. 61-62 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/1249067).

16Morrill & Stancill, “Amway, The Yager Way.”

17Carter, p. 35.

18Matt Novak, “The Untold Story of Napoleon Hill, the Greatest Self-Help Scammer of All Time,” Gizmodo.com, December 6, 2016 (https://gizmodo.com/the-untold-story-of-napoleon-hill-the-greatest-self-he-1789385645); Dylan Howard & Andy Tillett, The Last Charles Manson Tapes: Evil Lives Beyond the Grave (Skyhorse Publishing, 2019).

19Wead, “How The Amway Tool Business Began” (https://dougwead.wordpress.com/2009/04/14/amway-and-the-tools/).

20Obituary of Billy Bernard Britt, January 2013 (https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/newsobserver/name/billy-britt-obituary?id=12439515).

21“Coniguiliaro, Dominick & Pat,” Amway Wiki (https://www.amwaywiki.com/Coniguliaro,_Dominick_%26_Pat).

22Wead, “How The Amway Tool Business Began” (https://dougwead.wordpress.com/2009/04/14/amway-and-the-tools/).

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my book, which I wrote in part to take my mind off climate anxiety.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

💌 Feedback to share or want to say hello? Hit reply on this email or leave me a comment on Substack.