Afghanistan: another history that we failed to learn from.

We were doomed to fail in Afghanistan because we had no idea what we were really doing there.

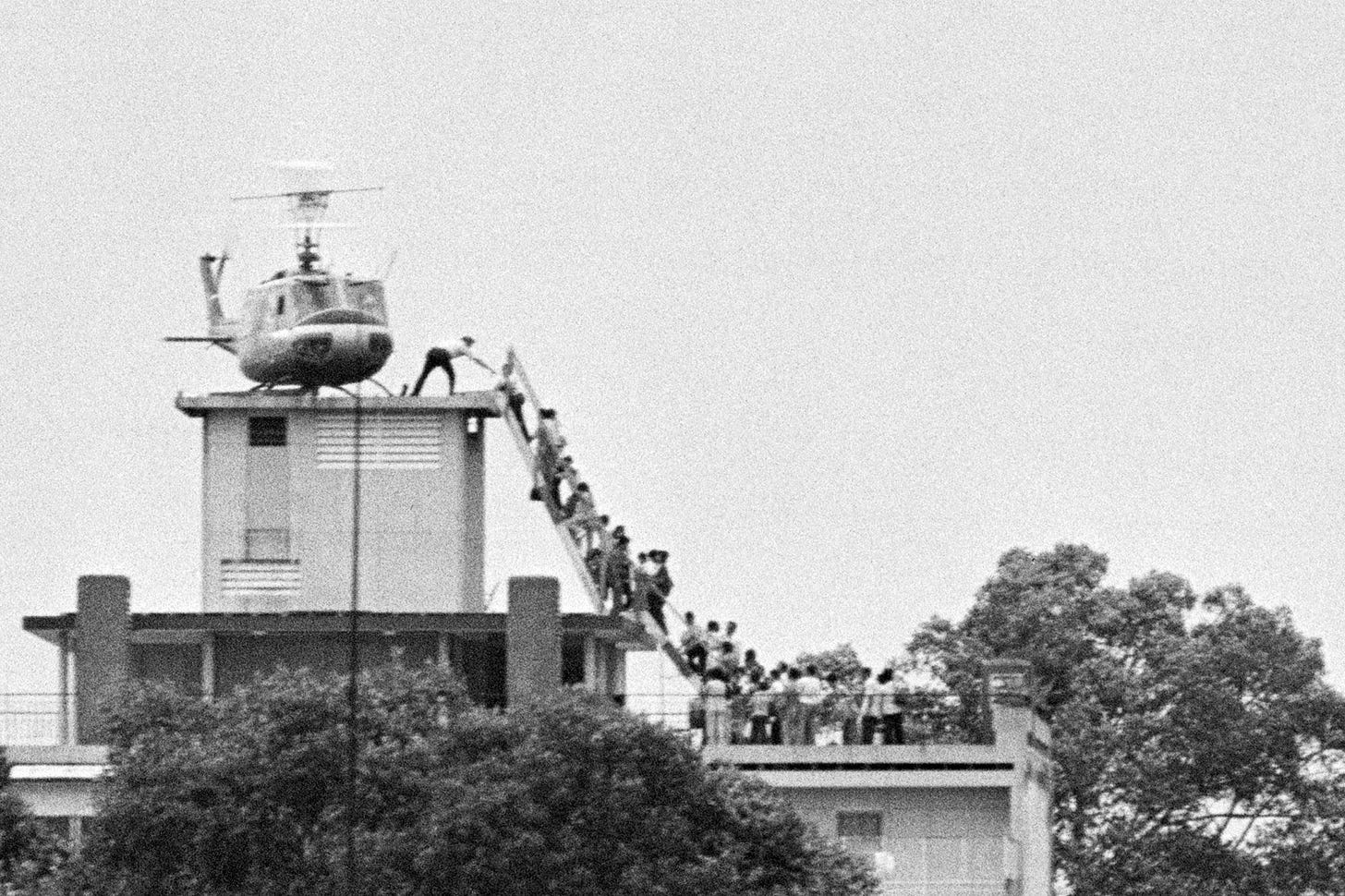

Yesterday, August 15, 2021, the Taliban recaptured Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, after a lightning offensive that followed the withdrawal of U.S. forces from that country after 20 years of war. The parallels between this event and the fall of Saigon, the former South Vietnamese capital, to North Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975 are so numerous as to be overwhelming. The photo at the top of this article shows South Vietnamese allies of the U.S. and their families desperately trying to get on one of the last helicopters to leave Saigon before Communist forces move in. It’s a very famous photo. Just scan social media today for the 2021 version(s) of this photo: cars lined up, filled with people trying to get to the Kabul airport; Afghan translators cowering in despair; the Taliban forces closing in on the capital.

No one who knows anything about the history of the Vietnam War should be at all surprised at what happened yesterday. (I teach an online class on the Vietnam War that covers this subject). The only amazing thing is how little we Americans learned from it, and how badly we managed to botch the Afghan conflict in the first place. We did not understand why we went into Afghanistan; we also did not understand why 9/11 happened, who the Taliban were, and what threat they really posed to our national interest. Even beyond questions of history, a basic boneheaded error in strategy underlay the entire Afghan conflict: we had no clear objective, which means we had zero hope—absolutely zero—of ever achieving it. You can’t “win” what you can’t, or won’t, define.

I remember the day we started bombing Afghanistan. It was October 7, 2001, less than a month after the September 11 terrorist attacks. U.S. special forces were already in-country, having dropped in only days after the attacks; I remember a September 2001 headline of the newspaper the Oregonian (that’s how long ago it was, we still had newspapers), which read, SPECIAL FORCES HUNT BIN LADEN. Americans were overwhelmingly in favor of military action against Afghanistan because it felt, to most of us, like “retaliation” for 9/11. President George W. Bush knew this. A few days after 9/11 he visited the smoking rubble at the site of the World Trade Center towers and crowed through a bullhorn that “The people who knocked down these buildings will hear from all of us soon.” Cue the bombers, and eventually troops. Everyone knew this was what was going to happen.

What isn’t generally known is how flimsy the plan for the Afghanistan project really was. Bush had only the vaguest notion of who bin Laden was before September 11, and the Taliban, the ultra-conservative Islamist sect that had controlled Afghanistan since 1996, was known to him in only the vague terms it was known to most of us, from the media. They repressed women and blew up ancient Buddha statues. Oh, and they gave shelter to bin Laden and his Al-Qaeda terrorists, who fled to Afghanistan in 1998 when, under U.S. pressure, no other Middle Eastern country, including Sudan (his former host), would take him. Bush had no preexisting grudge against the Taliban and nothing that he wanted out of an Afghanistan adventure except the positive public relations of retaliating for 9/11, and, if it could be brought off, the death or capture of bin Laden himself. There was no grand plan for Afghanistan. Tommy Franks, the U.S. Army general who planned the invasion, basically threw it together in a couple of days. It may as well have been written on the back of an envelope. Contrast this with the years-long planning for Operation Overlord, the U.S.-led invasion of Nazi-occupied France in 1944.

Part of the problem was that neither George W. Bush (I call him Bush II) nor any of his chief advisers really had any clear understanding of why bin Laden attacked the U.S. on 9/11 in the first place. The Bush II White House told us it was “because they hate our freedoms,” but I don’t think they believed that moronic claim; bin Laden didn’t give a damn about our freedoms. But it might have been a sound-bite oversimplification of something they really did believe, which was, perhaps, that all terrorists coming from that part of the world were a basically monolithic enemy with intractable grievances against the United States that no one really wanted to delve deeply into. Bush II did frame the Afghan invasion as the first front in what used to be called the Global War on Terror, with the word “Terror” standing in for any nuanced appreciation of who the enemy was.

Bin Laden’s true reason for attacking on 9/11 was as shallow and stupid as it was narcissistic. He did it to draw the United States into a retaliatory invasion of Afghanistan, which, in bin Laden’s fevered mind, would ignite a new jihad along the lines of the one in which he had participated during the 1980s, fighting the Soviets who had invaded Afghanistan in 1979. In bin Laden’s grade-school level grasp of geopolitics, the Soviet-Afghan war was the proximate cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. He wanted that same thing to happen to the United States. This motivation was narcissistic because, typically for bin Laden who saw himself as a messianic figure, it placed himself and his Islamist cronies in the central role of world history: Communism collapsed because the Islamist fighters who flocked to Afghanistan in the 1980s to join the jihad made it happen.

In reality bin Laden was small issue to the Afghan war of the 1980s. The mujahedin, the Afghan resistance against the Soviets, was happy to accept the money and material support rich Arab world donors like bin Laden were willing to give them—this was before bin Laden was stripped of his personal fortune—but they rather resented what they called the “Arab Afghans” who horned in on their turf on the battlefield, treating the war like a tourist junket and a basic training camp for their own little ax-grinding projects, like, for example, the Chechens’ long-standing conflict with Russia. Bin Laden claiming credit for the Soviet collapse was simply ludicrous. Yet this was the twisted reasoning he used to inflict the deadly attack on the United States. You would think someone in the Bush II White House might have considered this rationale.

The Afghanistan mission was muddled from the beginning. What was the objective? Defeat and destroy the Taliban? Defeat and destroy Al-Qaeda? Pop a cap in bin Laden? “Rebuild” Afghanistan, which had already been in a state of constant warfare for 23 years before 9/11? All of these? If only some of them, which ones? If one of these objectives was achieved, were we willing to let the others go? The closest thing I ever heard to a coherent objective was to “prevent Afghanistan from being a base for future terrorist attacks against the U.S.” That’s good as a sound bite, but what did it really mean as policy? It gets fuzzy around the edges. Bush II seems to have interpreted it as meaning, establish a pro-U.S. government in Afghanistan and prop it up by military means until it could stand on its own. That’s surprisingly close to the mission three U.S. Presidents (Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon) said we were on in Vietnam. We utterly failed at that objective. Bush II himself, in 2000, campaigned against the idea of using the military on “nation-building” projects. He forgot that promise pretty quickly and went on to be the most enthusiastic “nation-builder” through military means in U.S. history.

The leaders who followed Bush had every chance in the world to redefine the mission—perhaps as a means of ending it—but they chose not to. Barack Obama’s failure in this regard is particularly egregious because, unlike the empty-headed Bush, he was smart enough to know better. Having succeeded in at least one of the ostensible objectives of the war, that being the termination of bin Laden, Obama went all-in on “nation-building” in spite of any evidence that it would work as a long-term strategy. Would bin Laden’s assassination in 2011 not have provided a golden opportunity to reassess the whole mission and adjust if necessary? Apparently in Obama’s mind it didn’t. Trump seems to have taken the “base for future terrorist attacks” rationale pretty literally. He reportedly wanted to try to ramp down the war several times during his term, including at the very end, even after he’d been defeated for reelection, but was persuaded not to because, you know, “another 9/11.” But he could not, and did not try to, articulate any tangible benefit to the American people from an open-ended military commitment in a country that has resisted conquest by outsiders for centuries.

Most of the hand-wringing and lamentation now going on about the collapse of the fragile pro-U.S. Afghan government to the Taliban in the past few days stresses the monstrous nature of their regime, and the betrayal of pro-U.S. allies within Afghanistan. There’s no question that the Taliban is a dark, dreadful, repressive and monstrous government, completely toxic to any commendable human values and beyond the pale of acceptable conduct. But if the rescue of the Afghan people from the Taliban was ever our mission, it didn’t start out that way. The overthrow of the Taliban government was the objective of the Northern Alliance, the anti-Taliban coalition of ex-mujahedin whom Bush II and Tommy Franks co-opted as a proxy army in the fall of 2001 so we wouldn’t have to send as many U.S. troops. The Taliban became an American enemy not because of the horrible things they did to the Afghan people, especially women, but because they sheltered bin Laden and Al-Qaeda.

In short, the disastrous war in Afghanistan, which I think we can say now that we lost quite decisively, came about as a result of a fundamental failure by American policymakers to understand even the slightest nuance of history in this region. We did not understand why bin Laden attacked us, we didn’t understand who the Taliban were (and are) and how they differed from bin Laden and Al-Qaeda; we failed to understand where terrorist attacks come from, what “nation-building” means and how it’s done, or even what the basic role of the military is. This compounds the preexisting failure to understand the Soviet-Afghan war of the 1980s or Afghanistan’s broader history, why it fell into chaos in the 1970s, and how every great power attempt to co-opt or control it has blown up in the face of world leaders from Alexander the Great to Leonid Brezhnev. We don’t even understand what’s going on in that iconic photo from 1975 of the helicopter lifting off the roof in Saigon.

The Afghan war was many things: a tragedy, an agony, a trauma, a horrendous drain of human and financial resources, a political quagmire for us, and another stepping stone on the dizzyingly long and painful road for the Afghan people, whose misery seems bound to continue. But, for Americans at least, it was also a history assignment. We flunked it. Grade: F. Total failure. So long as an honest reckoning with history remained stubbornly outside the realm of anything our leaders were willing to consider, we never had a chance.

☕ If you enjoy what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

💌 Feedback to share or want to say hello? Hit reply on this email or leave me a comment on Substack.